YouTube link to the interview.

Transcript on New Science’s website.

Thank you to Graham Bessellieu for editing and to Ishaan Koratkar for the transcript.

In this conversation, I talk with Jacob Trefethen, who oversees science funding at Open Philanthropy, allocating about $100m/year. The discussion reveals how philanthropy makes decisions about which scientific research to fund, with Open Philanthropy's unique "hits-based giving" approach aiming for asymmetric upside.

Jacob shares insights on neglected research areas like Strep A (which causes half a million deaths annually yet receives minimal funding), the limitations of AI in accelerating scientific progress, and the challenges of balancing trade-offs when deciding between funding immediate applications versus more speculative basic research.

The interview offers a window into how Open Philanthropy allocates resources to potentially transformative science, from funding researchers rejected by traditional systems to debating whether certain scientific approaches deserve long-term, substantial funding. Throughout, Jacob provides a thoughtful perspective on what effective science funding looks like and how scientific institutions might evolve.

Topics discussed:

On Open Philanthropy’s decision process

Is it possible to make expected value calculations for basic scientific research?

Non-profit funding vs for-profit funding

Why the NIH rejects grants

Jacob’s “PhD” working side-by-side with two biochemists for 5 years

Today’s system of federal funding are not supporting generalists

How will AI affect the pace of scientific progress?

AI Baumol Disease

Can AI speed up aging research?

The wisest people Jacob & Alexey know

The future of science in academia

How Open Philanthropy uses neglectedness to make funding trade-offs

Jacob’s advice and views on purpose

Jacob’s favorite joke

Introduction

ALEXEY GUZEY: Good to see you, Jacob.

JACOB TREFETHEN: Good to see you, Alexey.

TREFETHEN: How have you been?

GUZEY: I've been good, good. Traveling around. Good to visit San Francisco, as always.

TREFETHEN: How long are you here for?

GUZEY: For a few days, I think. Flying to the East Coast afterwards. One of the main reasons I'm here is, in fact, to talk to you.

TREFETHEN: I'm honored. Well, thank you for coming by. Thanks for coming to make it easy for me.

On Open Philanthropy's decision process

GUZEY: You run science funding at Open Philanthropy. You spend a lot of time thinking about global health R&D and more basic science.

TREFETHEN: And we have a process where program officers and I have to agree at least 50% of the time. So, in fact, we end up agreeing quite a bit more. Probably more like 75, 80% of the time, currently.

GUZEY: That's kind of a brilliant way to structure this, actually.

TREFETHEN: That's– yeah. I think it might get the best of both worlds, because we are trying to take bets with these grants that have asymmetric upside, hopefully.

Hits-based giving is a framing that we'll often use. We care about the 5, 10% percent of grants that are really, really epic at the end of the day. And it's totally fine if the rest of the grants that we fund don't end up leading so much. So within science, especially, where you can't really predict the future very well, that model, I think, is going to outperform from a social impact point of view something that is more structured.

We have a highly autonomous system. You could argue that it's always about the margins of how far you go. NIH or NSF or Wellcome Trust – or pick your other funder – will often have peer review that does maybe give you more signal. We steal the program manager-type role from offers a little bit – of you have one person who has a budget and they have a lot of autonomy within it – to get the benefits of "you can't get vetoed". POs [Program Officers] cannot veto each other's grants with certain very limited asterisks. And that's wonderful because you don't have to persuade people.

GUZEY: Yeah.

TREFETHEN: You know, of course, PO performance gets assessed over time. So, at a yearly level, you can't disagree more than 50%, and then at a longer term level, if you're making lots of grants that look way above the bar set by global health charities, then Open Philanthropy should allocate more money to that program. It's a slightly more complicated long run system than I'm painting. But anyway, we think it gets the best of both worlds. Overall, my opinion is that science funding does involve too much… a little bit too much peer review, probably. And we're in one direction of like really little peer review. Program officers can decide "I would like to get external peer review" on something. And they often do because they cannot be experts in everything they fund.

GUZEY: This is interesting to me because I've been thinking about this a lot. And I also had experience like running a science organization, funding science projects, right? And I used to talk about how terrible peer review is beforehand. And then in retrospect, the first thing that I ended up instituting was peer review because I was so scared of making decisions. And it's like, well, I'm not a specialist, and then I had always tried to make sure that everyone agrees on what we're doing. In retrospect, something like 50% is a great idea.

I also immediately start to think about like, okay, what would be the dynamics of the system where, like so you say we have a program officer and they don't have to commission peer review, but they can, and they want to, and – I'm like, okay, if you just have the system, then over time, probably what's going to happen is that it's going to tend towards like commissioning peer review becoming the norm. And then not asking for peer review will be kind of weird, even if technically you're not like you don't need to. And just because like, again, people are pressured to minimize risks. And then you can always blame others if you commission peer review versus not. But they also like, again, this gets me back to this 50% benchmark. If you notice that you have like 80%, 90% agreement, then this is a signal to you that maybe you're doing too much peer review, which is like a signal that would be absent if you didn't have this benchmark for how much we should be agreeing.

TREFETHEN: That's interesting, because that's actually not the implication that I take.

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: I think I would correlate my opinion more with program officers at Open Philanthropy than peer review scores from external experts, would be my guess. Which means that the implication... the implication would not be right. Another downside of having such an autonomous system with – at the moment, the only real checkers being me, and in some cases, Emily Olsen and Alexander Berger at Open Philanthropy – is that you end up fitting too much to "am I [points at self] going to give the stamp of 'I agree' or not?" So you should do less peer review, you should spend more time with Jacob. So I worry about that. I don't worry about the peer review one.

We also hire people who are quite… who are not shrinking violets. We're hiring people who want to change the world. They're going out there and they believe in stuff.

Are there other dynamic parts of the system you think could go wrong and how I've described it, though?

GUZEY: People trying to please their boss is always a huge issue. But yeah, there is probably not that much you can do.

Is it possible to make expected value calculations for basic scientific research?

I think for me, like, my immediate thought here is it seems really hard, if not impossible, to do any kind of expected value calculations if you're funding science. And so you mentioned that – I think I'm just really confused about how this actually works.

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

GUZEY: Because like, I myself don't trust the calculations for things like deworming or like malaria nets, even. They seem like... Very, very fishy to me. But then if we're thinking science and basic science and —

TREFETHEN: It's interesting you chose those two examples, where people have looked at them more. I wonder if that's an availability reason you chose those two.

GUZEY: I mean, I saw the tables that GiveWell was providing for deworming impact estimates. And there is like, a hundred effects. And then, these are only short-term effects. And then, like, for malaria as well.

TREFETHEN: Deworming looks at long-term, but yeah, I agree with the point you're making. I'm just wondering if there's, the point you're making is downstream of it being very difficult to know anything about the world.

GUZEY: I mean, yeah, yeah, basically it is, but the point I'm making is that even for things that seem much simpler than assessing expected value of basic science, I'm still pretty skeptical about them.

TREFETHEN: Got it, got it. I'm with you.

GUZEY: And then we get to basic science, and to me, it's like, well, I mean, this has got to be impossible to do here. And yet somehow…

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

GUZEY: Like, how does that work?

TREFETHEN: So, it gets way easier the closer things get to application to put rough quantifications on them. So, we're funding an efficacy trial of – we were just talking about TB vaccines. We're funding an efficacy trial of a TB vaccine in adults, and we can really constrain a bit better the probabilities of "do we think that it will detect efficacy in a given range, given the design of the study, given previous trials in TB?". We have a little bit of a base rate to go off of. If so, do we think that it would become a GAVI vaccine? So, it would be GAVI-supported in lower-income countries? Do we think the Indian government would—

GUZEY: But this is also, like, very applied, like, so...

TREFETHEN: Totally, I'm going to look around.

GUZEY: One of your grantees just got Nobel, right, in Chemistry: David Baker. And you were very proud of starting to fund him back in his lab, back in 2017.

TREFETHEN: Not me personally, my colleagues.

GUZEY: Your esteemed scientists – biochemists – Chris Somerville and Heather Youngs, who I'm going to ask you about afterwards as well.

TREFETHEN: Oh, okay.

GUZEY: Also, sorry if I'm pushing too much on this, but, like, is there an Excel table somewhere in the annals of Open Philanthropy where Chris and Heather, like, calculated the expected value of giving a grant to David Baker and it came out to be larger than distributing malaria nets in Africa? Or was it just – he seems like a really brilliant person working on something very exciting, we should support him?

TREFETHEN: We almost always... So, nowadays, well, I'm trying to figure out the way to answer this. We almost always will have a spreadsheet of some form.

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: Now, what weight we put on that spreadsheet, versus qualitative factors of other forms?

GUZEY: Yeah, because I remember, Holden has this blog post that I keep returning to a lot where he talks about the expected value calculations and their weight in decision-making of when you're doing hits-based giving, right? And the inherent limitations in any kind of expected value calculations.

TREFETHEN: The calculations are always an input. They're always a tool that we try and use. The benefits they hold... If you can make a believable one, is that you can try and set consistently budgets across cause areas that are very different.

So, for example, Open Philanthropy does not do all basic science. You know, we could give all the money away to basic science, but nowhere near that.

GUZEY: Yeah.

TREFETHEN: And to do that, we would have to be persuaded of some quantitative reason to do it. I think it's actually quite hard to make the case that Open Philanthropy should do... I think we might do about 700 million of grant making this year. We should do 700 million in basic science, given the cases you can make for the, you know, global aid policy program we have. The cases you can make for lead reduction that's nothing to do with vaccines. You know, the cases you can make for factory farming is something that is a sort of current really messed up part of our society that you need to get rid of. So, you need some way to do a comparison between causes. The more quantitative you can make it, in my opinion, is great if the numbers reflect anything in reality. I think the further that you go back towards basic science with no intended application, the harder that gets.

You can rely on some things, though. You know, like, we exist within a context. And that context includes the existence of the NIH. That context includes the existence of HHMI. That context includes... The existence of, you know, the Allen Institute. So, it's not like that if Open Philanthropy doesn't exist, basic science won't exist. We're playing at a margin. And we can try and look at what are other actors doing and can we get any sense of how valuable that is in comparison. And I think you can make educated guesses about what a good basic science grant looks like from working backwards from potential applications. And this is a... You know, you've got to be careful. Because you never know what the true theory of change will end up being. But I think it's usually productive to have a theory of change. And, you know, if you look at —

GUZEY: Right. Like, what you're saying is that you don't know how exactly the thing you're funding will end up being useful. But if you literally can't think of a way that it will be useful, then this fact is informative compared to whether you thought there's five different ways something might be useful.

TREFETHEN: Yep, absolutely. And, you know, the reason we wouldn't fund something that's really stand out, that might be cross-cutting, is sometimes simply located in, well, would this get funded by the NIH?

And, you know, you mentioned David Baker and Institute of Protein Design. They had... They... We are not the cause of David Baker being David Baker. You know, David Baker's been supported by– He's a rock star being supported by many people, by many funders, I mean. The grant that we made at that time came from... So this is maybe apocryphal, because I was not in the room. I'm going off of secondhand. But, you know, Chris and Heather seeing Baker present these ideas, assuming, since it's so cool, that he would get funded by conventional federal actors, coming back around later, he still haven't got the money. And it's like, what the heck? And engaging in more detail of, okay, what would it look like if we made a pretty large grant to the Institute for Protein Design? And I believe in that case, again, you should ask David Baker and Neil King as well – get them on the show – but my colleagues, Chris and Heather, were pitched a certain thing and said, "that's a great thing." It was to do with flu vaccines and vaccinology, and sort of applying frontier techniques of protein design to that. But then asked, "okay, wonderful, David, by the way, like, what do you really want to do? That think you can't get funded?" And I believe David Baker was then like, "well, actually, really, I want to do this methods development. So that I can sort of work on protein design at a fundamental –" So deep learning wasn't quite the paradigm back then, probably. But, you know, various machine learning techniques to work on protein design. But, you know, he was – He didn't fit the box of – His background did not fit the box of NIH would give him $10 million or whatever. that... And then Chris and Heather were like, amazing, do both. Like, here's $6 million for that, $6 million for this. And, you know, that's not something that we do with every grantee, for sure. That's not our... But it's something that philanthropy can do. And the reason that looks so good, even quantitatively, relates to the fact that... That he couldn't get funded elsewhere.

And I get more nervous when we're just like, okay, look at this really hot shot person, give them loads of money, – this doesn't always counterfactually look that hot to me. Because the hot shot person often has access to lots of money. So you got to have a more specific story about, their background doesn't quite match what they want to do. Or, you know, their funders have not come to...

GUZEY: If someone wants to get science funding from Open Philanthropy, it's easy for me to go and try to get funding from a bunch of other different places and get turned down by all of them.

TREFETHEN: I mean –

GUZEY: Because otherwise Open Philanthropy will ask you, "well, why are you coming to us?"

Non-profit funding vs for-profit funding

TREFETHEN: It's kind of a horrible aspect of nonprofit funding, that–

GUZEY: Yeah.

TREFETHEN: That it's the exact opposite of if you start a startup and you try and raise money. If anyone hears on the grapevine, if you're a VC and you hear "they're about to get funded," you're racing to try and get your money in.

GUZEY: [laughing] Yeah.

TREFETHEN: Because you're like, "oh my God, there's no financing risk. Incredible." Whereas nonprofit dollars are so scarce, and when you care about counterfactuals, you can't— We don't care if our name is on something. We care about the impact. So it's a huge win. If someone else can fund something, it gives us more firepower to fund the next great thing we want to. But it is way worse from a PI's point of view and from an executive of a nonprofit's point of view. It's pretty... It's really... The dynamics are kind of messed up in that way.

Why the NIH rejects grants

My colleague, Matt Clancy, who works on innovation policy, sort of made a grant and set up a collaboration with the UK government on meta-science grants, which they're now evaluating right now. And I think you can get benefits of having one pipeline, but multiple funders with different perspectives. And sure enough, with the NIH program, there's just a lot of stuff that... I mean, there are many familiar reasons why NIH grants get rejected that you or I or another funder might not agree with. And some of them are that a given scientist doesn't have enough experience in a given area. That's like a classic reason to get rejected. And I don't think that's a great reason in lots of cases. Another is that there's not initial data that shows that what they're trying to do will probably work, and it's basically too ambitious and too risky. Very common. And not the kind of thing that we would rule out a grant for. And in fact, some of our best grants look like that.

So if you can use existing grant pipelines and look at the work that people have put in to write those proposals, I think that can be a great thing to do. It can't get you all of the best grants. Because sometimes you have to... You know, scientists often are trained by the system to break up problems into NIH-fundable units. And if you talk to a professor and say, you actually don't have to work within that... And you really try and think together through, like, "what could it look like if you worked on this?" You can end up with quite a different grant proposal. So it's not a be-all, end-all. Just use the existing pipelines. But it's a pretty good start. And there's stuff... You know, if I was a new science funder sort of trying to get my feet wet, I think it's a great way to start. Because you see, well, before I try and revolutionize the system, what is the system currently doing? I need to sort of know that before I actually know what I'm doing. So you can get a more grounded sense of your disagreements with the system by doing it.

Jacob's "PhD" working side-by-side with two biochemists for 5 years

GUZEY: So what did you learn from Chris and Heather?

TREFETHEN: I mean, it's... I don't know how to condense that into an answer. Because we've worked together for the length of a PhD for me. So I've had, you know, weekly meetings with them—

GUZEY: But I guess there is maybe a little bit more context to make it somewhat easier. This person, like, doesn't have a science background, right, and they are scientists with long careers in biochemistry. You ended up, through the years, you went from not really knowing anything about scientific grant-making and not having a background in science to overseeing a big science portfolio. I wonder if there are some key mental things that you learned. Or is it... Or is it less that, and more you just spent years reading grant applications and talking to them? That is just the accumulation of all of this is what enables you to do your work now? Or...

TREFETHEN: The accumulation of talking to Chris and Heather for many years, it does enable me to do my work now. That's also true outside of some scientific perspective and talking to other people at Open Philanthropy, which is a kind of hub for thinking about effective philanthropy. So I don't want to short shrift other people, too. But about scientific grant making, yes. I mean, we've just gone over a hundred plus grants that have been made I know really well. And that's... I haven't made them. And I haven't been qualified to make most of those. But I've discussed them. I've tried to come up with objections to why we shouldn't do this. Try and do that all the time to be generative or to... Some... Occasionally it will be a useful input into changing direction of something or expanding a budget.

I think the sort of high-level things— I'm just reflecting now on what high-level things I've learned from Chris and Heather. I mean, one thing that's really... They have such a unique relationship with each other. And they disagree a lot. And that is very valuable to watch as someone coming from the outside, that you can have quite different perspectives, even with very similar shared information state. And that cuts against the sort of spreadsheet approach to things. You really can be right there in the trenches with each other and still disagree.

Now, I don't want to overstate that because we've tried to quantify the disagreement, of course. And so we've done exercises like, even if you can't say how good an expected value something would be, give an ordinal ranking of your grants. So in a given year, put your grants into buckets. Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 3, Tier 4, Tier 5. And we've done exercises where I've done that for science grants. Chris has done that for science grants. Heather's done that for science grants. Katherine's done that for science grants. Ray's done that for science grants. And... Sorry, for their own grants in those cases. I'm going to recall the numbers wrong. But the ranking between Chris and Heather is more correlated. It's fairly correlated. It's not random. They kind of agree at the end of the day on quite a lot. The standard deviation of tier is something like 0.6. I have to look back. I disagree a bit more, interestingly. But overall, don't disagree that much. And, you know, what is that sample? Well, that sample excludes anything that we didn't make a grant to. So there might be more disagreement located in the things that never get a tier. That's very possible.

But, yeah, it's great to see... I've seen a deliberative, reflective process play out every week in an hour and a half or hour-long meeting with agreement and convergence and diversion. That's probably been... I mean, that's been very fun, for one thing. And we – I mean, Chris and Heather, but other colleagues too – cover such a broad area. That's another really interesting part of what you can do as a philanthropist. I mean, you could as other financing entities. You could as a VC as well. But, you know, their background is not in biomedicine. They're biochemists. But that background means that they have a kind of generalism across lots of forms of basic research that would end up being relevant to vaccines, drug diagnostics, you know, vector control tools. But also, you know, medical papers, also structural biology, also this, that. The background is enough to get you in the door to then read all those papers. But... the generalism is quite deep in a sense. You know, there's a huge amount out there. And you can't be an expert in all of it. So if you are trying to be opportunistic, do the highest social value things, and, you know, jump at this gap here, this gap here, you almost necessarily have to be a scientific generalist. Yeah. I don't know if I answered your question.

GUZEY: [thinks]

TREFETHEN: Well, by the way, if you're going to pause, I'll say more. [Chuckles] That's the danger.

Today's system of federal funding are not supporting generalists

The systems of federal funding are really not set up for generalism. Usually – I mean, there's some cases you can pick – but, you know, peer review from your peers in your field is the absolute opposite of generalism. That's notable, when you're able to do organizational design from the ground up, that that is where you end up going is, I think, partly in reaction to the current system.

GUZEY: Yeah... I have this crackpot, semi-crackpot thesis for a nonprofit or for a science grant-maker where the thesis of the org is zero peer review. Just take one person and they just decide whether to fund, like, science projects or not to fund. And that's it. And that's... And they're not allowed to seek external peer review. [laughs] It's a countermeasure. And they're probably going to end up funding a bunch of crackpots and a lot of things that don't make sense, but—

TREFETHEN: I'm generally— one of the sort of, I don't know, almost like meta-level organizational design principles I'm quite a big fan of is – and I think that is inherited from Alexander, the CEO of Open Philanthropy, who talked a lot about this – is flexibility. So the reason I don't like that is why ban someone? Don't ban someone. The reason to ban someone is if you need to jostle them out of the system they're otherwise going to get drawn into. But... Yeah. Just give people freedom. Give a peer freedom to... If they want to get external peer review, they can. And, you know, their manager might get mad at them if they make fewer grants because they're doing too much...

GUZEY: Well, I mean, the reason I'm thinking about that is because, again, I think I'm just thinking about, like, what happened to me. I never intended to be... Doing grants by committee. And that's what I somehow, like, found myself doing because I was just, like, too scared to...

TREFETHEN: Did you have anyone in your life, a board member, who could say, Alexey, "why are you doing this, why are you doing this?" Because I think that's a nice role. You know, I have weekly one-on-ones. That's a nice role. If you have someone in your life saying, "why are you doing this," then it can give you permission. That might be a cheaper way than banning. Why are you trying to ban yourself and stuff, Alexey? You just have, you know, a one-on-one every week. Yeah. Say, "I found that I'm doing this." And then in your one-on-one, whoever you're talking to will say, like, "why are you doing that?" And then you'll say, "because I'm scared." And then they'll be like, "then don't do that." Problem solved. We did it in a week.

GUZEY: Yeah. That has not been my experience.

TREFETHEN: Oh, really?

GUZEY: Yeah.

TREFETHEN: Fair enough.

GUZEY: Actually, I mean, this part probably should really not be included, but I think, like, when I'm thinking back on New Science and, like, large parts of what went wrong is that I didn't really have Heather and Chris figures who I could just go and talk to about what I'm doing. Like, I just didn't have anyone to go to and figure out and talk to about what I was doing.

How will AI affect the pace of scientific progress?

GUZEY: AI FOMO?

TREFETHEN: AI FOMO? I have the opposite. I think, if I know what you mean... I feel like every time someone tries to draw me into AI, I'm like, ooh.

GUZEY: Okay. So you have the opposite of AI FOMO?

TREFETHEN: I'm sure that's been true or false in different ways at different times. So I don't need to claim that's always been true. But...

GUZEY: But at the moment?

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

GUZEY: I guess it's, like, especially in San Francisco, I feel like whenever I come to San Francisco, all of the people I know here, well, except for you, perhaps, are doing something related to AI. You know, there is a couple miles from here, there is Anthropic, another few miles away from here, there is OpenAI and – you know, the Intelligence Age is almost upon us – all of these things, and so you're not... not drawn at all to, like, go and become a technical manager at Anthropic or at OpenAI or something like that? So feel free to... We can skip this question.

TREFETHEN: No, no, no. It's all fair game.

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: I am not, as a descriptive fact, drawn by that.

GUZEY: You don't want to be in the room where AGI is developed?

TREFETHEN: I... Not in that framing. No. That sounds horrible. I mean, that sounds... I think that urge that people have... I think that the urge that people have is often trying to meet a personal emotional need rather than a societal need. And I would love if people could meet that personal need through things that don't affect other people's lives quite so extravagantly. So I would see that – if I were following that urge, I would see that as maybe not the best way to make career decisions.

But, you know, I do think there's a lot of incredibly intellectually interesting things happening in all forms of alignment research and also developing new models and also biological foundation models and all this. There's many different frontiers that are being pushed incredibly rapidly. And that is something that I do think...

Well, you know, I haven't left San Francisco in a few months now. But the – I think San Francisco and the rest of the world, they're really in different head spaces, really very different head spaces about what the next five years are going to look like. And I'm sure that my social circle – I hang out with a lot of friends who work in AI or who have strong views one way or the other on different political problems with AI. So I'm sure I'm influenced by all of that in the way that I think about problems. And, you know, I do think in the case of medical progress, I've been thinking more recently about trying to...

Should we – you won't like this – I'm just going to go back to talking about my current job instead of "should I leave and do whatever you want me to do?" But how should we adapt our portfolio now in the context of potential changes to medical research that are driven by AI progress, and in the context of whenever we make a grant, the impact that actually happens from the grant is many years down the line. So you actually should be thinking ahead rather than thinking the most important thing this year is [gestures] this, so let's do this. You know, you actually have to backchain from years in the future. And I think that I probably do have different views about that that are informed by being in San Francisco than if I – you know, if we were a biomedical research grant-making organization based in...

GUZEY: How does this affect your grant-making?

TREFETHEN: So far, not much. And so I wonder, is that a mistake? But the thing that I often turn to is I think you can make educated guesses about...

Let me phrase it differently. Let's say that AI progress in a broad sense of language models, but also foundational biology models – but also this, that, and the other – continue to make progress at a clip. Biology and biomedicine as a science does indeed drive medical progress. So do you assume that medical progress will move forward at the same clip? And if not, why not?

I think one way to break down the question is, which parts of the system of medical research will become bottlenecks in a world that AI continues to progress really fast? I think you can make educated guesses, certainly at the five year level about that and maybe the 10-year level about that. I can give you my guesses, but I think basically the inference is that those are, if you care about the societal impact of whatever you're trying to make in biomedicine, you should relatively speaking focus more on those bottlenecks potentially, rather than just diving into the hot AI stuff that everyone's sort of already pushing ahead really fast.

GUZEY: Right... So, what are those things?

TREFETHEN: Well, I'm of course not sure. I don't know. But my educated guesses are that—

GUZEY: Because I've been, I mean – this is also for me, very interesting, right? Because I spent a lot of time thinking about biology, a lot of time thinking about AI, and I am – I'm not even sure... how exactly will the kind of science being done change?

Because in a way we have already – especially in biology – we went through this really dramatic transformation where people would spend their entire PhD sequencing a single gene, and now we can sequence an entire genome for a few hundred dollars. In a lot of ways, the biomedical research productivity has already gone, like, just thousands, millions of times over.

In a way everything changed about the way we do biology, but also nothing really changed, and I feel like I'm personally very confused about this and we'll just, like, see the same thing – everything will change in 10 years, but also, kind of, nothing will really change and...

TREFETHEN: I have the urge to get a bit more specific about what changed and what didn't because I don't think that all fields of biology changed at the same rate, and it depends what productivity means because I agree with you that over the course of one generation of a scientist's life – let's take it back to Chris and Heather.

Chris Somerville, my colleague, was one of the main guys behind Arabidopsis and, you know, the senior author on the main paper, this was a lot of his career of the model plant organism that gets used a lot. The first time they sequenced the genome of Arabidopsis, it costs – I think they had like a $100 million grant. So in a way, maybe it costs that. I don't know literally how you'd attribute the sequencing. I don't know how much you got, but, like – an absurd amount of money.

And now you can sequence Arabidopsis for, say, $100, probably less, probably way less, I don't know. But you're talking about real orders of magnitude. The question for me then on, and so it must be absolutely just such a trippy experience for him of, you know, it wasn't that long ago we did the first, like, that was 25 years ago, like, not long.

Similarly, with, more recently protein folding, you used to maybe spend a whole PhD trying to work on one protein, and now you can at least take sequence to structure and do really well very quickly. Yeah. Or you can't necessarily—

GUZEY: Yeah, like validate things in a few weeks, right?

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

GUZEY: Also, we went from, whatever, like, 200 weeks to 2 weeks, something like that.

TREFETHEN: Depends specifically on—

GUZEY: Okay, sorry, I don't know enough biology, but also more than an order of magnitude.

TREFETHEN: Right, I agree. We're not there on lots of things. You know, that's proteins, and that was built off the protein databank. Are we there for carbohydrates? Are we there for lipids? I haven't seen it. And are we there for protein function? Well, not yet, no. Function's harder to define than structure. Like, in some contexts, a protein acts this way, and in some contexts, it acts that way. Function's kind of what we care about. There's a long way still to go.

When we talk about productivity improvements, you can point to these things that have three orders of magnitude differences. The thing that I always try and backchain from in my seat now – I'm not saying this is the only reason to do science – but in my seat right now, that I care about science for health impact, for people, starting from the premise of everyone matters equally, and everyone's life matters equally. I care about productivity that's harder to benchmark. I'm like, "show me the new life-saving drugs at the end of a pipeline", and that's a really lagging indicator. It's a cruel one in a way, but I'm extremely confident that we don't have a 1000x improvement in approval of life-saving drugs.

You're looking more at the level, okay, what does someone actually do now? What does this structural biologist do now, versus what they did five years ago? Like, what are they actually doing day to day? And are they producing discoveries of similar magnitude, different magnitude? It gets a bit more complicated. I don't think that AI will sweep through as quickly.

If you talk to biologists about this, then the classic thing that I'm sure you've heard all the time is like, well, "Guess what? Alpha Folder is built on $10 billion of previous data collection in the protein data bank." So, you're looking around, you're like, "where do I have a really high quality data set that could get a similar kind of AI-driven, sudden improvement." And everyone's doing that now.

But then there's an even deeper question, which people in San Francisco talk about – which hasn't probably [laughs] made it very far beyond San Francisco yet – which is more around synthetic data or more around designing reasoning agents or scientists that you can then instantiate in a virtual university with a million of them, where they debate and publish papers and all that stuff. So that, um, I don't feel able to make good predictions about that world, because I don't think we've even got anywhere near that, but I think in the next few years, probably we could well do.

I feel like we can, you know, like here's one thing that I think will be a block in five years, uh, good targets. Like, we've got really good at designing something that binds to a target, but everyone's going off to the same targets in cancer. There aren't that many known validated good targets, so you can chuck as much money as you want, but if you don't understand how the system works... Similarly, take a brain disease – Alzheimer's – we have such poor measurement of what's going on in the brain that, do I think we're really going to get good targets in the next five or 10 years, even with magical AI from the sky? Well, no, because no one's going to open up their brain and be able to take the relevant measurements probably.

I can tell the story the other way, if you want me to, but I've rambled for a while... that's – [smiles] ah, I'll do it.

The story the other way is that, "oh, you don't need high quality data." It turns out that if you have a genius from the sky, you can actually learn so much from YouTube videos and learn about how physics works. You can have perfect laws of physics. And then when you have perfect laws of physics and you've just only read PubMed or only ingested such and such dataset of human biology, you can figure out what's probably going on up there, even if you never take any measurements and therefore you can make a perfect Alzheimer's drug. I can't refute that. It's possible that you can have wonderful simulations with our current level of data and you don't need to collect much more. That's not where I would currently place my bets. So I don't think we will have a great cure for Alzheimer's, even with magical AI before it goes through other real world data collection. But I could, I mean – what do you think about that?

AI Baumol Disease

GUZEY: I think I agree with you pretty much on all of this. I think one... I guess I think about Baumol's disease and indeed, AI will make sub-problems of problems we care about dramatically easier to do. Like, we care about [gestures] human health and for that we need, say, drugs. And part of getting a drug that works is predicting protein structure at some point to help with – I don't know enough details – but it's like part of a bigger problem. And there is like 20 sub-problems, and AI, maybe for five of them, AI will just make them free, essentially, but then you're still left with 15 problems, which probably cannot really be sped up, and that end up just occupying the rest of the time. So I do wonder whether there is some kind of an upper bound on how much AI can speed things up, because I know even at the end of the diseases just progress at a certain rate.

TREFETHEN: Totally, totally.

GUZEY: And there is this rationalist and empiricist frame, and rationalists say, "yeah, we can just think very hard, predict," and I think I'm just like, especially for complicated systems, now, you need to actually go and do the experiment. Until you run the experiment, you just genuinely don't know.

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

GUZEY: This makes me very sad, because it's...

TREFETHEN: It doesn't make you happy? We have so much to learn.

GUZEY: Uh, it makes it—

TREFETHEN: We're alive way before the beginning of biology.

GUZEY: Yeah, yeah. I mean, this makes me worried. I think I used to...

I kind of bounced around from thinking that – I mean, the original thesis behind New Science, in a lot of ways, was "AGI is not near." And everything will take decades. We need to really figure out how to make sure that science works well, that basic institutions of science are well functioning for the decades ahead.

Then I, like, went through a phase where like, oh wait, yeah it [AI] will change everything in the next few years, so none of this basic stuff of science and institution stuff makes sense, and now I'm back to this point of "oh, shit the world is going really slow." And like, yeah, AI will be strong, but like, it won't change the world. Again, every – in some ways, everything will change for some problems for which AI is really good at, and for other things, nothing will change.

This makes me very... I mean, this is why I'm thinking about institutions of science again, right? [laughs] because I'm like, "oh, wait, we need to plan for decades ahead and make sure that science works well decades ahead" and that all these, like, Alzheimer's – indeed my impressions are that we just we don't really understand, like, biology. We don't really know how to measure things. The brain is still – it's just like I'm... I feel mortality very acutely now, again.

TREFETHEN: What do you mean?

GUZEY: I mean, literally, you know, if I don't expect singularity or anything like that happening anytime soon, and if I really think that at the end of the day, you need to run clinical trials for things you really care about and they take years, then you don't really have that many shots on the goal. We have 50 years, 60 years? How much can you do in 50, 60 years?

[laughs]

TREFETHEN: Well, I mean, the...

[stands up and grabs Her-2:

The Making of Herceptin, a Revolutionary Treatment for Breast Cancer]

I haven't read this book, but I think it's gonna cheer you up.

[tosses the book to Alexey]

Here's my gift to you. I just bought it for me, but you can have it.

So I think, oh, no... am I thinking of the right, is that Imatinib? Which is that?

Yeah, I don't think that [Imatinib] had a phase three trial. I think it was so good in the phase two – but someone will correct me in the comments – so it was so good in the phase two, that they just approved it. It would be unethical not to.

And so the happy world for you would be, we have such magical AI systems that an AI system predicts, "by the way, if you run this in a clinical trial, then there's a 84% chance it will hit endpoint XYZ in 10 years, and we're highly confident it's not gonna cause neuroinflammation and it's not gonna harm your brain for XYZ reasons." And then maybe you'll be happy taking it to slow down progression of Alzheimer's. Now, there's a whole other set of questions of, will the policy world adapt to that and in what ways? I think in the case of prevention, you probably will be slower. In the case of treating people who will die of a disease, I think the policy response may be quite quick of "okay, this AI system spat out a prediction that it's probably gonna work. Do you wanna be in the trial where you might be in the control or just take it?" I think people would be like, "okay."

Anyway, there's my optimistic case. That said, I'm actually more in your...

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: What do I currently believe? Yeah, I think some things still take – you know, Alzheimer's, if you're taking a daily drug to prevent progression of it, which no one is basically currently, but if we had a future drug – that totally could have safety problems, you know? So do you want to take it before you've seen, how someone in a clinical trial did after five years, after 10 years? I'm like, not sure. It's sort of pretty slow moving disease. So we might just have to wait for that trial. And it's, that takes time. I think the thing I, if I would cheer you up in a different direction, it's that, the—

GUZEY: [laughs] I like how this interview started from me asking you about your work at Open Philanthropy into you just cheering me up, so I would continue to pray for the future.

TREFETHEN: [laughs] Well, I, uh...

GUZEY: [laughing] Please continue, I appreciate it.

TREFETHEN: Of course, one of the, um—

GUZEY: [laughs] I hope you're doing this for free...

TREFETHEN: [smiles] Oh, I assume I'm getting paid for this interview. No, one of the, you know, I was saying earlier about how it's frustrating that there are so few good targets to go after and everyone goes after the same ones. Well, the analog, the disanalog of that in the case of products that help people in lower and middle income country settings, but not so much in high income country settings, is that there are plenty of probably good targets that haven't been explored that much. And, you know, if you're... it's way easier to study a bacteria in a lab and to learn a lot about it as well than to study a human system. You might be able to find quite a lot out about that bacteria, and have quite a few potential antigens that you could go after with a vaccine, for example.

If I may squeeze in Strep A into this interview, because any time I'm allowed to, I will. Strep A is a bacteria that you've probably been infected with many times. I have been. It causes strep throat. Do you remember the last time you got strep throat?

GUZEY: I used to get strep throat a lot.

TREFETHEN: It's very annoying, so mostly it's annoying but sometimes it—

GUZEY: I actually was in the hospital twice when I was younger for it.

TREFETHEN: Totally, yeah, it can – it's real... kids end up in hospitals somewhat frequently for it, and can get an invasive disease where the strep bacteria spreads around your body, and it can cause lots of problems, and it can cause many deaths, actually, in toddlers.

In addition, in lots of countries, if you get infected many times, there's an autoimmunity, there's a molecular mimicry issue. Your body's trying to attack the pathogen, but actually ends up attacking your heart valves. So you can get acute rheumatic fever or long-term rheumatic heart disease, which leads to early cardiac problems and death. And if you add up all the problems that strep A causes downstream, the best estimate – which isn't a great one – the best estimate that we've got is that it leads to about half a million people dying every year.

GUZEY: Oh.

TREFETHEN: And you know, when we loop back around to can you even make any comparison between basic science of [gestures] this form or this form? And how will you know what's better than the other? Well, you can look at neglectedness as a pretty good lens and very few people are working on strep A, very, very few.

If you look at the total amount of R&D funding dedicated to trying to make a vaccine, for example, or include if you want some more microbiology and basic stuff, and epidemiology of where's rheumatic heart disease happening? The best estimate I've managed to pull together is that there's maybe $1 or $2 of R&D funding per year of life lost due to infections globally, okay? So you shouldn't have an intuition for what that means, but you're gonna get a comparative one in a second, which is that for cancers, it's probably about two orders of magnitude higher. So more like $200.

So that doesn't tell you anything immediately because maybe it's impossible to work on strep A, and so there shouldn't be any money spent on it, but I'll give you a hint. It's not impossible to work on strep A! There's quite a lot you could do. And if there were more scientists really laser focused on the problem, you know, there's loads of unanswered questions at the level of what makes a good antigen. There are maybe seven leading hypotheses.

GUZEY: This is so weird.

TREFETHEN: [nodding] It's very weird, very weird.

GUZEY: How come?

TREFETHEN: There's a couple drivers. I mean, the deaths are mostly happening in lower middle income countries. So not exclusively though, invasive disease can get you anywhere.

GUZEY: Yeah.

TREFETHEN: That's a big driver. So another reason is the FDA banned trials for 30, 40 years, and that ban got lifted in 2006, I think. So that sort of meant that it was hard to build a career in the field or lots of vaccine companies don't have programs where they've looked at.

Then in addition, because of the auto-immunity issue, you want to be sure that you're not creating problems with a vaccine. With modern tools, I think you can be pretty sure you're not, but there's a question of what data package will I have to get to prove that there are no safety issues?

Then there's a question for vaccine developers of efficacy. It's pretty easy to run a trial against pharyngitis strep throat, because people get that all the time. You and I are at risk of getting that in the next year, so we could enroll in a trial, let alone kids who get it all the time. So you only need maybe a thousand people to run a good trial with that, but if you care about preventing rheumatic heart disease, if you care about preventing necrotizing fasciitis—

GUZEY: Yeah, that takes so long.

TREFETHEN: Proving the link is, you know, in a trial, very difficult because the incidence is too low. You won't accrue enough cases of necrotizing fasciitis where it's in your legs and eating your flesh and every hour it moves another inch kind of thing because it's rare enough.

Can AI speed up aging research?

GUZEY: So I should be pessimistic about the future again?

TREFETHEN: No, you should be optimistic because- well, sorry, sorry, you should be pessimistic unless you want to get involved in the fight against strep A.

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: I think if you and your viewers got involved, we could really take a swing at it because you could test a bunch of vaccines for sure, you definitely could.

GUZEY: Unfortunately most of our viewers work on things like biosecurity and monitoring, things like that. Instead of taking real problems.

TREFETHEN: Oohhhfff, you're insulting your viewers? Wowww, wow. That's interesting. Interesting. Those are real prob—

GUZEY: No pandering to viewers.

TREFETHEN: [laughs] Any other swings you want to get in at them? What else are they working on?

GUZEY: [laughs] All kind of stupid shit.

TREFETHEN: I mean, basically what's the limitation on this problem? There's scientific limitations, human capital limitations and money limitations.

GUZEY: Yeah. No, but it is striking to me – but like the thing that I keep returning to is these things that I do not see a way of speeding up. Like at the end of the day, will we be able to use AI to predict that, or shorten the length of clinical trials from 10 years or 20 years to down to a year?

This makes me think that maybe we'll solve, in some basic way, aging, but we'll solve it before all of these diseases. Like we'll understand how the body falls apart, but not...

TREFETHEN: So, I don't think we will solve aging before we solve strep A. I think that...

GUZEY: Also, sorry, sorry, but since I asked you about this, an immediate follow up is – since you mentioned that health impact is what you really care about at Open Philanthropy—

TREFETHEN: Yes.

GUZEY: Are you guys then trying to solve aging?

TREFETHEN: We have given grants many years ago to Irina Conboy and Steve Horvath. We've tilted out of that grant-making for neglectedness reasons. There are now lots of companies popping up funded by wealthy people trying to work on aging, so the neglectedness of the field looks way less.

In fact, a lot of the – you know, what do we have? Money. What can we do? Give people money. That's sort of our job. A lot of the money flowing into the field is now bottlenecked on people, that it's just pumping out salaries as far as I can tell. So for aging right now, we've pulled back. But we've done some in the past, yeah. It's interesting that as a sector [aging] is so company focused relative to other sectors, nowadays, but I think that's for various sociological reasons.

What is aging? Infectious disease is a part of aging. Inflammation is a part of aging. Heart disease kills however many people, and if you could solve heart disease, you'd solve aging in some way. There's these pendulums that swing in discourse of like, broader society is often focused on specific diseases, and people rightly, 5 or 7 years ago, were like "hold on, in the case of aging, are there cross-cutting functions and cross-cutting drivers that if you could solve those would help with all sorts of diseases?". I think that's a really valuable lens shift. Sometimes, I wonder if we've gone too far in that direction now, of like, well actually you could cure cancer and you could cure heart diseases. That'd be pretty cool. So, I'm not sure at the margin, where I'd go there.

I expect that the stuff we're funding because it's so much more neglected, if we weren't giving support to those scientists, then they're not getting money elsewhere. So, that makes the case much easier from an impact point of view.

GUZEY: Right.

TREFETHEN: You don't want to make a strep A vaccine together? I think we could bash that one out. I think we could do that, I mean, not you and me —

GUZEY: [feigning disappointment] oh

TREFETHEN: But we could help scientists who are doing that.

GUZEY: I thought we'd... [looks down]

TREFETHEN: Okay fiiiiine, you and me.

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: You twist my arm. We can work on strep A. You know, I didn't want to work on strep A until this interview, but if you're going to keep pushing me like this.

GUZEY: I mean you keep bringing it up. Every time you talk to someone, you keep talking strep A, you know—

TREFETHEN: I'm a real freak like that.

GUZEY: Maybe it's time to put your money where your mouth is.

TREFETHEN: Yeah.

The wisest people Jacob & Alexey know

GUZEY: Who's the wisest person you know?

TREFETHEN: Oh, my gosh. Who I know?

I don't know. Maybe – can I give boring answers? Probably, like, my friend Sarah back at home. And my mom. I don't know.

GUZEY: [laughing] Wonderful. Tell us about Sarah. That’s such a fun answer.

TREFETHEN: I haven't discussed before this interview if she would be...

I don't know. I just feel like when you, what is wisdom? I feel like I'm often seeking a – what would someone with good character do in situations that I'm in? And sometimes I think of Sarah.

But what is wisdom? Let's see. There are many people who I either know or have a more parasocial relationship with that I view them as bringing out the best in me, but I don't know if that's always wisdom. Well, which lane do you want me to pick? People I don't know or who I do kno? Or, no, no, no, I'll blur the edges:

[gestures] Seemay Chou, Prachaya Vasti, who are making Arcadia, I find inspiring from up close and from afar. As you know, we sort of hang out in circles that talk about changing scientific institutions and that are trying to be more ambitious and different with how science is done. And they are really living it. They are living it. They've created a whole new institution that is iterating like crazy on doing experiments and how should you rethink publishing, and how should you, uh, rethink stopping investigating something? Like at what stage do you stop? Because of the opportunity costs, you know, you shouldn't investigate everything forever. When you do stop, what can you publish so other people can know? They’re actually living a lot of what I sort of think about. So that’s really cool.

[gestures] Heidi Williams, she is an economist who I think has this presence that brings everyone along with her, and she’s just so prosocial and public goods-focused.

[gestures] A friend, Nan Ransohoff who runs Stripe Climate. She actually has this sort of similar to Heidi description I just gave. She somehow makes the world actually move towards creating whole new technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. I'm sort of like, what? How?

I feel like it's dangerous to give out one's idols because then they might know. And then they might – I have to – okay, I'll hold back on some of them. Virginia Woolf though. She can know.

GUZEY: She's coming for you now.

TREFETHEN: Who do you think is the most wise?

GUZEY: Tyler Cowen.

TREFETHEN: Tell me more.

GUZEY: When I look back over the years, who are the people who I wish I listened more to? He is like at the top, just like consistently somehow tells me things that I think I should have thought about before. And then I ignore him. And then a few years later, I'm like, oh wait, Tyler told me about this a few years before.

TREFETHEN: It's a good way.

GUZEY: Yeah, I noticed that whenever I think about things that are very difficult, I ask myself “how would Tyler think about this?” more often than for any other person. He’s kind of a scary person. He's too wise.

TREFETHEN: [laughs] Good thing to aim for, I suppose.

GUZEY: So how will science be different in the 21st century?

TREFETHEN: Too big, too big.

GUZEY: Role of academia?

TREFETHEN: Role of academia?

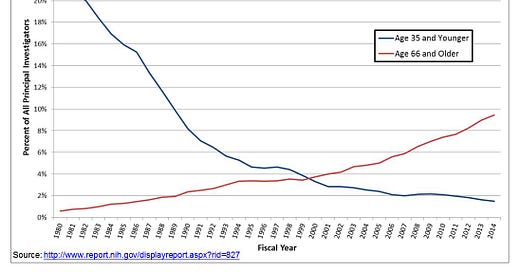

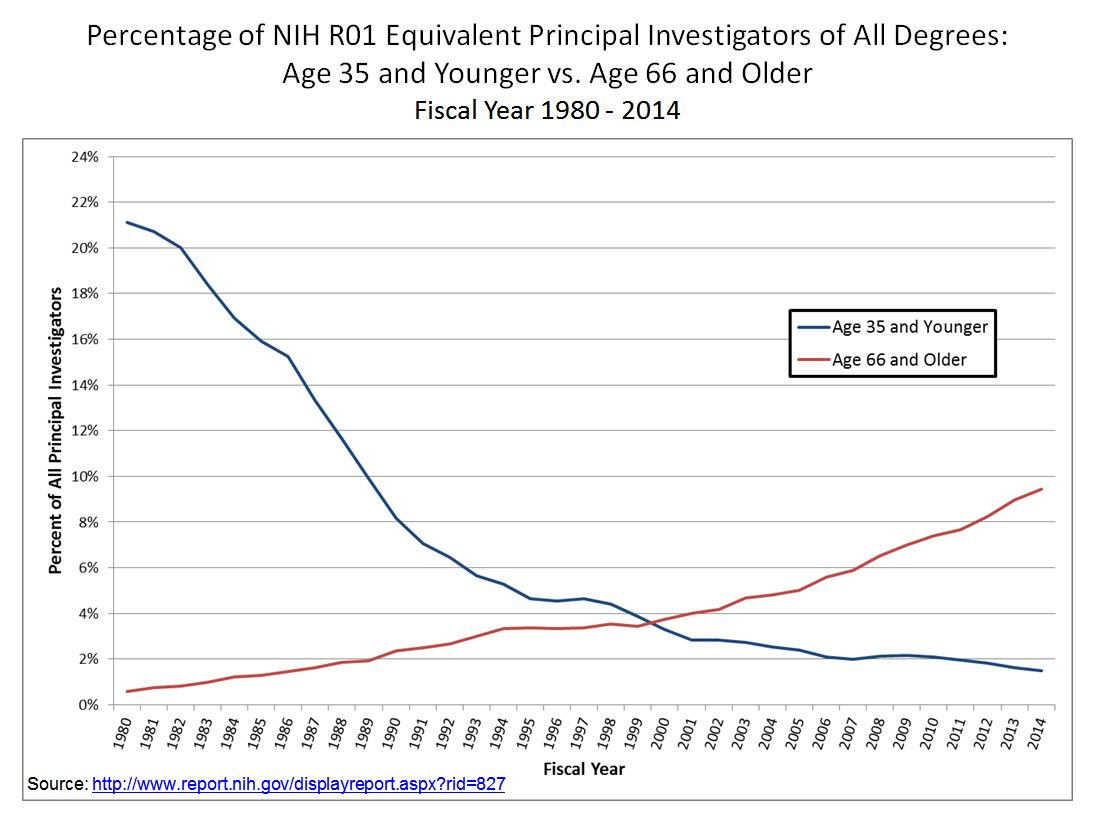

GUZEY: You mentioned that for aging, for example, for sociological reasons, it's a problem that often for-profit companies are funded by people who really care about the problem directly affecting them, perhaps. And then right then I know, I guess I think a lot about context for this in my head. I can't stop thinking about this graph of NIH funding distribution. We're like, ages 35 and less like this, and just 65 more like this.

And I think at this point, it's like primary investigators ages 65 and older are getting funded at 7x the rate of those 35 and younger, I believe, something like that. And it keeps getting worse. So this makes me—

TREFETHEN: [nods] That is crazy.

GUZEY: Yeah, this is just like bonkers. I think a lot about what Tyler Cowen said, with Emergent Ventures, where you just fund really young, talented people. And Tyler Cowen once said that it seems that young people are getting accelerated actually, because the internet just allows people to learn much more, to get up to speed a lot more.

Tyler pointed out an example of chess where Magnus was pretty young when he became world champion and the person who Tyler expects to be the new world champion is like 17 or something crazy like that. And so the top performance keeps getting younger.

I was recently talking to a professor of physics at MIT and was asking him about the preparedness for research of undergrads and grad students these days. And he told me the same thing that because of the internet sometimes the best undergrads are better prepared today than like 10 or 20 years ago. So in my head, there is this thing about on one hand, it seems that naturally young people are getting accelerated and like they should be getting more funding and more support and like, should be getting up to speed faster. And like in software, obviously. Or, like even you [Jacob], you are now, whatever, like 30 or so. Maybe you look younger [laughs], but you're now running this big thing at Open Philanthropy, right? And on the other hand, it seems that academia is not reacting to that at all. In fact, it's like the professors are getting older and then there is this AI thing and I think it also pulls away the most talented.

For example, a bunch of the most talented grad students I know in biology who I would have expected them to go and become professors and they all – well, not all, but the most talented ones, a bunch of them – just started biotech companies immediately after graduating PhD, even though I would have been sure they're the kind of people who I think would like, for them, the perfect career path would be to become a professor around the lab.

And so I have all of these things in my head and I am famously a person who likes to criticize academia a lot, but I do wonder if there is going to be some kind of a trend where more and more research on the basic one will just be done by other sources, maybe it's going to be, you know, Tyler funds the 20-year-old and Open Philanthropy funds the person when they're 23 and then they're just now running their own lab doing whatever it is that they want to do, sidestepping the entire system. And then with the help of AI also like one of the things that I feel like AI will do is just amplify the top performers. Like in biology, if you don't need to... if the experiments are done by robots, intellectually intensive work is going to be more and more outsourced and individuals get more leverage as well. And so there is, I feel like this aspect. Anyway, sort of been rambling.

TREFETHEN: There's a lot of different parts of this picture, I think. Maybe a place to start is just me personally, and that's what I know best is my own life. And, you know, I view biology as one of the consolations of aging. There’s an unlimited nexus of different things you could know about cell biology, about different organs and diseases and all that, so that every year it feels better and better. It's so wonderful. The accumulation of knowledge. And I know so little, but next year I know a little more and then I know a little more. And that's sort of, you know, as I realize I will get older, that's been a nice field to go into because I think biology does actually sort of inherently, no, inherent isn't right, but it does reward accumulation of knowledge and connections rather than just raw “think my way through a problem” talent. So I think I dispute some of the premise in that I think some forms or some fields will have top performers of different ages. And then within any given field, you will get heterogeneity anyway. I totally agree with the punchline for what it's worth though, of even within biology, I don't think even the NIH wants the – who is the NIH? – But I think a lot of people at NIH probably feel quite awkward about how high the median age is of PI's getting grants.

And I mean, I view that as one of the big contributions of the work you've done, also of the ARC Institute, also of the meta-science community that's been building over the last few years as a kind of a broad group of people interested in trying to make science go better. Is this just highlighting this fact more and is the solution to that fact that you build more institutions that empower younger people sooner? Is the solution that you try and reform the NIH? Or is it somewhere in the middle? Like the Art Institute are put sort of in the middle of they're working with the existing universities in the area, Stanford and UCSF, and they work with Berkeley as well, I can't remember, but they're empowering certain people with much more resources and much sooner than you would. And that's great. So that's definitely a direction I agree with – sold, that should change. I don't know how it breaks down into what I would change.

Then... now I'm wondering what other parts of the question to pick up on. What will happen to academia broadly?

GUZEY: Okay. Proportion of revolutionary basic science done within like... Universities versus outside universities.

TREFETHEN: As I think through, well, what do I really believe about that question and what drives it? One thing that is coming to mind is how many of the discoveries of the future will come from big science or big collaborative efforts, like the Human Genome Project, like AlphaFold requiring so much of an institution to... be behind it and the compute and all of that, like telescopes. Pick your examples that are kind of big, big collaboration versus the discoveries that just won the Medicine Nobel Prize this year. I don't know that story well, and I'm curious if you do actually, but microRNAs – that was basically, you know, you can discover that in the 90s in a lab and that's kind of what they won it for. As I think through the big discoveries, the big discoveries... As I think through some discoveries from the last 30 years, a lot of the blockbuster ones do seem to have come from more of these big collaborations.

You could view the Baker Lab that way, even though it's one lab. You know, the Institute of Project Design has tens – or maybe a hundred now – of students and just a couple of professors, but a lot of those students end up getting faculty positions. They've been trained on their Rosetta tools. They end up using them in their new position, feedback in and build a tool. So how do you count that in terms of size?

I do think that purposefully set up organizations with, you know, more regular managerial structures than academia can outperform on some of those big problems. I mean, it's happening right now in fusion. Who's going to end up adding the most value, these new fusion companies or the big government funded projects or national labs? I don't know the answer to that. But I really... I wouldn't be surprised if, frankly, because of wealth accumulation due to tech as well, it was like there's some really rich people now. They can do that, you know, projects they want to do in a private company because we support property rights in America. So where does that wealth go is almost going to drive some of the answer rather than the more bottom up scientist led answers to the question, probably.

The future of science in academia

TREFETHEN: Do you have hope for academia? And if so, what kind of hope?

GUZEY: I have hope for undergrad part of universities. I think people, especially in Silicon Valley, underappreciate the value of a college degree funnily enough. But it's mostly because of the exposure. It's like a very nice track to be on where you can just like meet a lot of people, explore a lot of different things, talk to and meet a lot of professors, meet people your age, take any class you want. Socialize, have fun. But in terms of academia afterwards, I am... I mean I feel like I'm professionally obligated to say no in some way because I'm literally working on building new institutions of basic science.

But in a way there is... The way I think about academia now is that it's like... Professional science. I think academia has always been really good at professional science and paradigmatic science. And it's probably going to remain actually pretty good at this kind of thing, whereas I'm personally just more interested in pre-paradigmatic research and generalists doing things like... Uh, I know it seems that like, this is kind of a stupid example, but like Darwin, right? Like he spent whatever, a couple of decades writing his Origin of Species and probably would not do well at all in academia and I think all of the researchers that I'm most interested in somehow don't quite fit in. They can't get funding. They are just too weird for academia. They work on things that are too long term, too poorly defined—

TREFETHEN: Is that right? Don't you like lots of... I think of the people you've told me you love before, some of them are doing pretty well in academia. I don't know if you want me to out them on the podcast.

GUZEY: Well, we can, we can always cut things out.

TREFETHEN: Ed Boyden is doing pretty well.

GUZEY: That's the most ridiculous example you could have come up with. Because Ed Boyden, the only reason he's still in academia is because of you guys, because he was about to close down his fucking lab at MIT and then you came in, Open Philanthropy and gave him a huge grant and now he's doing well and he recovered and didn't NIH literally reject him like nine times in a row. Like I remember he said that in some of his interviews that his expansion microscopy, now one of the most successful projects coming out of his lab, was literally rejected nine times before it got funded. By who? [motions at Jacob]

TREFETHEN: [laughs]

GUZEY: Open Philanthropy. I think that's a great example.

TREFETHEN: It's interesting that that's your narrative on it. Not that I had anything to do with that decision. So when we made the original grant to him, I wasn't there, but of course I'm willing to take the praise if you want to give it. It would be super interesting to ask him what he thinks would have happened to his career in the absence of that grant.

So I think what would have happened to expansion microscopy is a different question. I mean, expansion microscopy is crazy. I cannot believe how big that's gone. Like jeez, I can't believe it worked and it's gone so big. It's like, what? So yeah, that's one of those where you're if you make one of those grants, you can just pack it up and retire kind of.

But I wonder, I mean, he's so talented that in other ways that wouldn’t he have found something great to do with that? I don't know. Anyway, you know him better than I have, I've met him once in my life, so I don't know.

GUZEY: No, I think that's actually a very good question to explore. Like what, what would he have done? I do think academia is doing... like, he’s restricted as a result.

I mean – I actually – I remember like I used to lobby Open Philanthropy—

TREFETHEN: You once sent me an email saying you need to give Ed Boyden a hundred million dollars. And I said, thank you so much. Or maybe I ghosted you. I probably ghosted you.

GUZEY: I think I was sending this email to Holden, to you, to anyone at Open Philanthropy I had an email for. And you guys never did.

TREFETHEN: Not yet, not yet.

GUZEY: Yeah. And I think it would have been better for the world if Ed Boyden had a hundred million grant to start his own thing instead of being in academia.

I think a lot about the fact that he still lives within that system. Where he has to like constantly churn out papers, constantly apply for grants. He's constrained by the fact that he has students who are with him for five years. I would really love to see if Ed Boyden just had like 20 years of funding for an institute. Like, what would have happened? And I suspect that something way more interesting would have happened.

How Open Philanthropy uses neglectedness to make funding trade-offs

TREFETHEN: When you talk about duration of funding and flexibility of funding, to a funder, what looms large are the trade-offs.

GUZEY: Yeah. Trade-offs, of course.

TREFETHEN: Unfortunately. Yeah.

GUZEY: I'm an Internet writer who just pesters people and sends them emails telling them to fund this and that. And you're the person who has constraints, who needs to make decisions, who faces trade-offs, the famous economics thing that sometimes features in our life.

TREFETHEN: Here's an example of a trade-off. If you give someone a four-year grant versus a 20-year grant, that's five times less money. Example: The UK biobank is so useful already, and we know it's going to get more useful over time as it accumulates more data. Does that mean that you should just endow it? Just give it as much money as an institution that can continue for decades, and don't faff around with all these grants that they have to write. And that's an argument that actually I find a bit more persuasive than pick your favorite scientists in 2024, give them 20 years of funding. Although I'm curious, how many scientists in the world would you think of the 20-year thing? Because, you know, for example, HHMI, how many investigators are there? I'm not sure, actually. But there's quite a few. You know, it's... It's a very limited set of science, but it's probably...

GUZEY: Three thousand?

TREFETHEN: Yeah. Well, hundreds of thousands, say. And that's... Okay. So that's already a lot. Would you halve it and double the period? Would you double it and halve the period? Or are you talking about there are five Ed Boydens in the world, and it ain't about the 500? Oh, okay. Interesting. So list them. Who’re your faves?

GUZEY: Do you have anyone except Ed Boyden? Michael Levin, perhaps. Tufts.

TREFETHEN: What would the annual size of your 20-year grant be?

GUZEY: For Boyden, yeah, probably between 50 and 100 million... a year.

TREFETHEN: [laughs]

GUZEY: [laughs]

TREFETHEN: That's beautiful. Thank you. That's really...

GUZEY: That's like 20% of your endowment, right? Something like that.

TREFETHEN: Yeah. But hey, it's a pitch. How would that get spent? So let's divide it out. How much is a postdoc's salary? How many people are in this lab?

GUZEY: Yeah, that seems...

TREFETHEN: I just think you get management constraints in labs. Like, you know, you...

GUZEY: No, that seems too much. How many people can he... Actually, that probably... No, that's...

Probably closer to the order of $10 million per year. I think if it were more than that it’s not just a Boyden thing.

[laughs]

We'll see if I'm brave enough to leave this in.

TREFETHEN: [laughs]

GUZEY: Hopefully no one who is considering giving money to my non-profit is watching.

TREFETHEN: If I were you, the productive line of inquiry, I would sort of advocate for myself is to just really scrutinize the trade-offs more. Because you can do a lot of damage with $1 million. You can really fund work that won't happen without it. And that work can be towards a goal that you think might...

In our case, we work on biomedical science. So towards a goal that you think might prevent tens of thousands of deaths a year, maybe hundreds of thousands of deaths. And the trade-offs get very acute when you're facing down the barrel of do we fund this marginal Malaria monoclonal antibody project?

We just funded Alassane Dicko in Mali to do a phase one to a trial that's basically never been done before, of a potentially transmission-blocking antibody that you could give maybe in combination with something that would have personal protection, too. And, oh my gosh, if that worked, just imagine. Right now, there's seasonal malaria chemoprevention that kids in many West African countries will get, which is taking preventive drugs that you swallow, you know, a few times, four months in a row. Kids hate the drugs. You find them in the trash. You know, like, not everyone finishes the regimen, all that. And they're not perfect. Even if you finish the regimen, imagine if you had one fucking — oh, sorry — one injection that protected you for a whole season, because you had a really good monoclonal and it involved a transmission-blocking component that reduced malaria spread to other people because there's fewer parasites in your body for every other reason. Then, oh my God, and guess what? That did not cost $10 million a year for 10 years. So the tradeoffs in science can be so intense because that's a great project. I'm very glad we funded it. And there's lots of other... That's not the only amazing project. There's many other ones, too. Some of them are in Mali, and some of them are in Thailand, and some of them, you know, they're not all at MIT. So, you know, if you're...

GUZEY: I think about this just... I'm just so much more interested in basic science and methods development. It just seems... Whenever I think about funding things, I always want to fund methods development, essentially. And so this is why I'm so excited about Boyden, for example.

TREFETHEN: Okay, let me sell you another one, that maybe we can meet in the middle on—

GUZEY: Again, I'm, like, I'm thinking about, like, the reason I'm, like...

TREFETHEN: So do you mean, like, tools as well? Like, microfluidic chips, do they get you going?

GUZEY: Maybe. I don't think I... After I said this $100 million a year thing, now I'm very worried about saying anything because that is very stupid.

TREFETHEN: No, that wasn't stupid. I was not trying to shame you for that being stupid.

GUZEY: I'm trying to think of, like, 50-year time horizon, something like that.

TREFETHEN: Yeah, I don't like the 50-year time horizon. I think the world changes too much. I'm into 10. You can get me at 10.

GUZEY: Yeah, 10, I'm just, like, at 10... Again, if we're thinking about really understanding how the brain works, really understanding how aging works, really understanding Alzheimer's, will we get there in 10 years?

TREFETHEN: I don't think we will, no.

GUZEY: Yeah, so why not think of 20 years? Because it seems like if we think about 10-year horizons, then we'll never find this Alzheimer's stuff.

TREFETHEN: But, you know, the trouble is, play it back. It's, well, let's say...

GUZEY: Are you saying that if it's not tractable within 10 years... Then it's just too early to be finding this problem, essentially?

TREFETHEN: No, no, no no. I don’t mean that. I don't mean that. I mean: if you're trying to attack Alzheimer's and you think it's a 50-year problem, the reason I would still try and think in 10-year chunks is that tools from other parts of biology, from AI, from whatever, will sweep in and hopefully be helpful in 10 years in a way that you can't predict now. So, if you just pick, I'm going to focus on Alzheimer's, I'm going to fund on Alzheimer's right now, but you don't yet have, you know, a clever probe that non-invasively detects XYZ that you end up getting in 10 years, then the work you did might not be that useful.

GUZEY: The way I think about this is if I think about 50 years for Alzheimer's, then this kind of... where the middle ground is, it suggests that pure Alzheimer's – pure biological Alzheimer's research – is just not the right thing to fund right now for the reasons that you outlined, and, indeed, they're like more basic methods development things that will in the next 10 years get developed, and then over the course of coming decades really affect how more object-level Alzheimer's research is done – is the right thing.